|

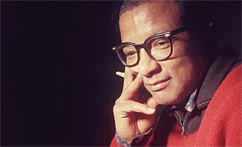

Duke Meets Strayhorn

As Told by David Hadju "Billy Strayhorn was my right arm, my left arm, all the eyes in the back of my head, my brain waves in his head, and his in mine." That’s Duke Ellington, describing a musical partnership that continued for 25 years, until Strayhorn's death from cancer and alcoholism at the age of 52, a partnership that produced some of the most beautiful, most important American music of the last century. The composer and pianist Strayhorn was just 23 years old when he met Ellington, already a major international star and leader of one of the world's most popular bands, for the first time backstage at an Ellington Orchestra performance at the Stanley Theatre in Pittsburgh in December 1938. David Hadju describes that first meeting: Shortly after midnight on December 1, 1938, George Greenlee nodded and back-patted his way through the ground-floor Rumpus Room of Crawford Grill One (running from Townsend Street to Fullerton Avenue on Wylie Avenue, the place was nearly a block long) and headed up the stairs at the center of the club. He passed the second floor, which was the main floor, where bands played on a revolving stage facing an elongated glass-topped bar and Ray Wood, now a hustling photographer, offered to take pictures of the patrons for fifty cents. Greenlee hit the third floor, the Club Crawford (insiders only), and spotted his uncle with Duke Ellington, who was engaged to begin a week-long run at the Stanley Theatre the following day. “As soon as my uncle introduced us,” said Greenlee, “I turned to Duke and I said, ‘Duke, a good friend of mine has written some songs, and we’d like for you to hear them.’ I lied, but I trusted David. I knew Duke couldn’t say no with my uncle standing there. So, Duke said, ‘Well, why don’t you come backstage tomorrow, after the first show?’ It was all set.” The next morning, Greenlee arranged to meet Strayhorn for the first time in front of the Stanley Theatre before the 1:00 p.m. opening matinee. The day was chilly but still, and a light snow fell on and off. Strayhorn was collected, Greenlee would recall, and looked properly ascetic—“He was wearing his Sunday best, but they were pretty well worn.” They watched the first show, a long set of Ellington Orchestra numbers peppered with a tap-dance act (Flash and Dash) and a comedy team (the Two Zephyrs), then found their way through the baroque old Stanley, eight stories high, with thirty-five hundred seats and three full floors of dressing rooms. Ellington’s dressing room was the size of a large dining room and, in fact, was set up like one: several place settings were arranged on a table, and there was an upright piano along one wall. Ellington, alone with his valet, lay on a reclining chair in an embroidered robe, getting his hair conked, eyes closed. “I introduced Billy, and we stood there,” said Greenlee. “Duke didn’t get up. He didn’t even open his eyes. He just said, ‘Sit down at the piano, and let me hear what you can do.'” Strayhorn lowered himself onto the bench with calibrated grace and turned toward Ellington, who was lying still. “Mr. Ellington, this is the way you played this number in the show,” Strayhorn announced and began to perform his host’s melancholy ballad “Sophisticated Lady,” one of a few Ellington tunes Strayhorn knew from his days with the Mad Hatters; as a trio, the group used to play a version inspired by Art Tatum’s arabesque 1933 recording. “The amazing thing was,” explained Greenlee, “Billy played it exactly like Duke had just played it on stage. He copied him to perfection.” Ellington stayed silent and prone, though his hair work was over. “Now, this is the way I would play it,” continued Strayhorn. Changing keys and upping the tempo slightly, he shifted into an adaptation Greenlee described as “pretty, hip-sounding and further and further ‘out there’ as he went on.” At the end of the number, Strayhorn turned to Ellington, now standing right behind him, glaring at the keyboard over his shoulders. “Go get Harry,” Ellington ordered his valet. (Harry Carney, Ellington’s closest intimate among the members of his entourage in this period, had played baritone saxophone for the orchestra since 1926, when he was 16 years old, and the two frequently traveled together to engagements.) “Wellll!” proceeded Ellington dramatically as he faced Strayhorn eye to eye for the first time, Ellington gazing down, Strayhorn peering up. “Can you do that again?” “Yes,” Strayhorn replied matter-of-factly, and began Ellington’s ruminative “Solitude,” once more emulating the composer’s piano style. When Harry Carney entered the room, Ellington stage-whispered, “Listen to this kid play.” Again Strayhorn declared, “This is the way I would play it,” and reharmonized the Ellington song as a personal showcase. Brazenly (or naively) the twenty-three-year-old artist demonstrated both a crafty facility with his renowned elder’s idiom and a spirited capacity to expand it through his own sensibility. The potency struck Ellington, Greenlee recounted: “Billy was playing. Duke stood there behind him beaming, and he put his hands on his shoulders, like he wanted to feel Billy playing his song,” Carney hustled out and returned with two more members of Ellington’s musical inner circle: alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges, thirty-two, a premier Ellington soloist since he joined the band in 1928, and Ivie Anderson, thirty-three, who became Ellington’s first full-time vocalist in 1931. As this group gathered around Strayhorn, “Things got hectic,” said Greenlee. “Duke fired off a million questions about Billy’s background and training and so forth. Billy kept playing from then on, mostly his own things—‘Something to Live For,’ which he sang, and a few others” (including a piece so new he hadn’t given it a title yet). Recalling the occasion in later years, Ellington focused on that moment: “When Stray first came to see me in the Stanley Theatre, I asked him the name of a tune he’d played for me, and he just laughed. I caught that laugh. It was that laugh that first got me.” However impressed he may have been by Strayhorn’s musical skills, Ellington was also struck by something visceral. The above was excerpted from Lush Life, David Hadju’s biography of Billy Strayhorn. |

Copyright ©2024 Seacoast Jazz Society, All Rights Reserved