|

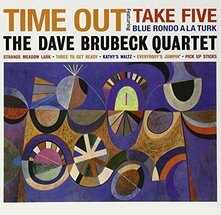

The Dave Brubeck Quartet: Time Out

The year 1959 has been called the most creative year in jazz. It was just four years after Charlie Parker had died and the very year both Lester Young and Billie Holiday passed. Jazz was now moving in a surprising and exciting number of new directions. Consider the classic albums that were released in 1959: the Miles Davis Sextet’s quintessential Kind of Blue, which introduced the concept of modal jazz; John Coltrane’s landmark Giant Steps, the complex chord progression of whose title track dazzled and baffled jazz fans and influenced every saxophonist thereafter; Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz to Come, the iconic free jazz album that featured a chordless quartet in a revolutionary turn that presented a whole new approach to jazz improvisation; the Bill Evans Trio’s Portrait in Jazz, showcasing an interconnectedness among three musicians that hadn’t been heard before; Charles Mingus’s Mingus-Ah-Um, an album filled with classic Mingus originals, a civil rights message, and a swinging, soulful, wailing band playing outstanding arrangements; and the album at hand today, the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Time Out, which presented a playlist of original tunes in time signatures not ordinarily used in jazz, the album that introduced alto saxophonist Paul Desmond’s original “Take Five,” in 5/4 time, which climbed the popular Billboard charts and was the first jazz album to sell a million copies. The Brubeck Quartet was eight years old in 1959 and included alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, who was in it from the beginning. (Brubeck had in fact met Desmond when he was in the military in 1944.) During a long residency at the Black Hawk jazz club in San Francisco, the group had also become highly popular on the college scene as it toured campuses and produced a series of related albums: Jazz at Oberlin and Jazz at the College of the Pacific, both in 1953, and Jazz Goes to College in 1954. Also in 1954, Brubeck was featured on the cover of Time magazine, an honor that embarrassed him, as he believed that Duke Ellington was more worthy of it. In fact, when he had the opportunity, he told Ellington, “It should have been you.” For a jazz musician, Dave Brubeck’s background was unusual. Born in the San Francisco Bay area, he grew up on a cattle ranch and had every expectation of following his dad into the family business. His mother, who had studied piano in England under Myra Hess and intended to become a concert pianist, instead ended up teaching piano as a way of adding a little extra income to the family budget. Dave and his older brothers, Henry and Howard, all took lessons from their mother. But while the brothers intended to become professional musicians, young David was less interested in that and in fact struggled in his lessons with his mother, having particular trouble with reading music. Brubeck’s career path took a turn when he was a student at the College of the Pacific studying veterinary science. The school’s Zoology Department head told him, “Brubeck, your mind’s not here. It’s across the lawn in the conservatory. Please go there. Stop wasting my time and yours.” And Brubeck did just that. The album Time Out was recorded at Columbia’s 30th Street Studio in New York City in three sessions: June 25, July 1 and August 18, 1959. Along with the pianist/leader were longtime collaborator and alto saxophonist Paul Desmond; bassist Eugene Wright, the one African-American in the group, who had joined the quartet a year earlier for its U.S. Department of State tour of Europe and Asia; and the phenomenal (and legally blind) drummer Joe Morello, whose drumming virtuosity helped make this particular project possible. The inspiration for a jazz album showcasing odd time signatures was said to have come during the quartet’s 1958 State Department tour, on which Brubeck observed in Turkey a group of street musicians playing a traditional Turkish folk song in 9/8 time, breaking the nine beats in each measure not into the expected 3-3-3 meter but into 2-2-2-3. It was this experience that influenced directly Brubeck’s composition “Blue Rondo a la Turk,” the album’s first track. “Strange Meadow Lark,” the second track, which begins with a piano solo, turns into the standard 4/4 time. “Take Five,” the most celebrated tune on the album, the one and only written by Desmond, features a solo by Joe Morello — probably the first recorded drum solo in the unusual 5/4 time signature. The tune was a huge popular hit for the quartet, emerging as the quartet’s signature tune and now an enduring jazz standard. The playlist includes two waltzes (3/4 time): “Three to Get Ready,” which starts out in 3/4, then alternates between two measures of 3/4, and two of 4/4, and “Kathy’s Waltz,” which starts in 4/4, then goes into double-waltz time before merging the two. “Everybody's Jumpin’” and “Pick Up Sticks” are both in 6/4 time. Following the release and notoriety of Time Out, it wasn’t long before other jazz groups began using such “exotic” time signatures. The avant-garde trumpeter Don Ellis, in fact, made something of a specialty of it in the ’60s, even venturing far beyond such tame expressions as 3/4, 5/4 and 9/8. But in 1959, what the Dave Brubeck Quartet did was novel. And, by the way, this music swung. —Terry MacDonald Track Listing (All composition by Dave Brubeck except “Take five” by Paul Desmond) 1 “Blue Rondo à la Turk” – 6:44 2 “Strange Meadow Lark” – 7:22 3 “Take Five” – 5:24 4 “Three to Get Ready” – 5:24 5 “Kathy's Waltz” – 4:48 6 “Everybody's Jumpin’” – 4:23 7 “Pick Up Sticks” – 4:16 Source: Wikipedia |

Copyright ©2024 Seacoast Jazz Society, All Rights Reserved