|

Some Reflections on Count Basie’s “New Testament” Band

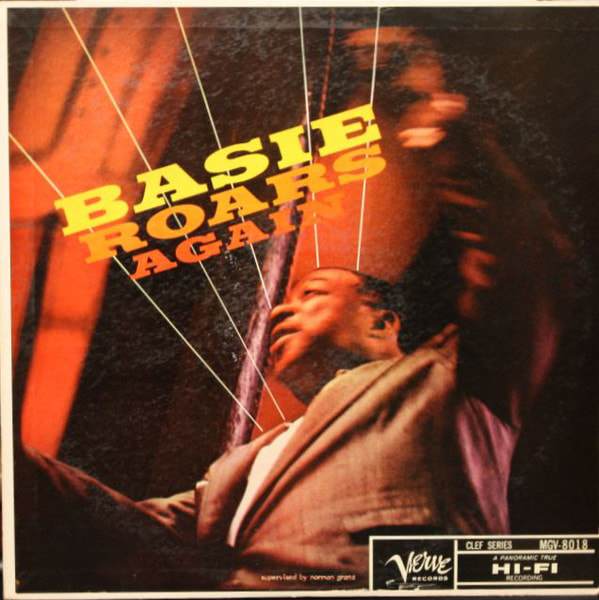

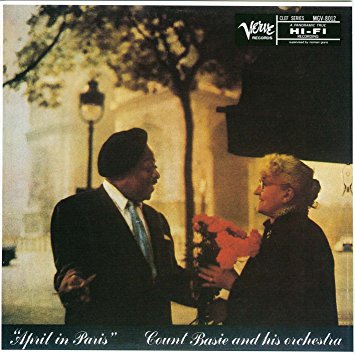

by Charlie Jennison Sometime in the spring of 1968, when I was an undergraduate junior at University of New Hampshire, local music legend Tommy Gallant took me to Lennie’s-On-the-Turnpike in Peabody, Massachusetts, to see the Count Basie orchestra. Lennie’s was not a large venue; the band was lined up on one wall with the piano tucked in a corner and the audience seated on folding chairs or at tables. I sat directly across from “Lockjaw” Davis, close enough to toss a spoon in the bell of his tenor sax, had I wished to do so. Marshall Royal, who I would meet and play next to sometime in the 1980s, was playing lead alto, Al Grey and Grover Mitchell were on trombones, Ed Shaughnessy played drums, and “Sweets” Edison was on trumpet, as I recall. Outside of my All State experience at Key West High School, I had never been right up next to a professional big band before, and the experience was overwhelming! Although at the time I was only dimly aware of the history of Big Bands, I later wondered how it was that the Count had managed to survive the late ’40s with his band and even thrive into the ’60s and beyond with an entire discography of hit albums. The history of the Basie band is generally divided into two periods—the “Old Testament” band, which lasted from 1935 to 1950, and the “New Testament” band, which ran from 1952 until Basie's death in 1984. The former orchestra recorded primarily on 78 rpm vinyl and was characterized by up-tempo riffs, the blues, and a host of star soloists, including Lester Young, Jo Jones, Buck Clayton and singer Jimmy Rushing, among others. By contrast, the latter band was more suited to the 12-inch LP era. The New Testament band played in a more laid-back, minimalist style that packed plenty of punch but no longer had to squeeze tunes into the three-minute duration of the 78 format. The band also no longer had to depend on a fixed group of musicians or soloists who knew the orchestra's unique material. This breakthrough was assisted by a new generation of skilled arrangers who stretched out songs and devised a streamlined swing without losing Basie's personality or character. Recently I came across an article by Marc Myers, who writes regularly for The Wall Street Journal and is author of Anatomy of a Song (Grove) and Why Jazz Happened. His blog, JazzWax, [1] is a two-time winner of the Jazz Journalists Association's best blog award. According to Marc, Basie encountered a few significant individuals during the dark period after the war when the economy and changing public taste made it difficult if not impossible to support a large musical organization like the Big Band. Those guiding stars made it possible for Basie to negotiate the rough waters and keep his band afloat, even though initially his group reappeared in smaller formats like octet, septet and even sextet, with arrangements crafted to make the ensemble sound like a larger group. In his autobiography, Good Morning Blues, Basie said he loved leading these small groups. However, he recalls his old friend Billy Eckstine, who led a powerful big band in the mid-1940s saying, "Man, what do you keep fooling around with little old one- and two-piece stuff for? Get your big band back together. Man, you look funny up there...” Additionally, Morris Levy, the owner of the jazz club Birdland, made Basie an offer. Levy managed to make room in the schedule for the Basie band and gave him an open-ended residency. In Godfather of the Music Business: Morris Levy, [2] author Richard Carlin writes, “According to some people—including Basie himself—Levy was central in reviving Basie's band... By guaranteeing Basie regular work at Birdland, Levy lay the groundwork for the resurrection of the band.” Birdland also was steady income for Basie, without the need to tour. This was welcome news to Basie and the band, since most of the musicians lived in New York at the time. Basie’s new “Birdland Band” personnel included Marshall Royal, Frank Wess and Frank Foster on saxophones, Henry Coker, Bill Hughes and Benny Powell on trombones, and Wendell Culley, Thad Jones and Joe Newman on trumpets, with Freddie Green, Eddie Jones and Sonny Payne comprising the rhythm section. It’s not clear if Basie owed Levy money and was working off the debt through his Birdland residence, or if Levy was doing Basie a favor to call in a favor at a later date. What is apparent is that Basie called on baritone saxophonist Charlie Fowlkes to hire the new band's musicians in the spring of 1951. The band needed new charts arranged for larger instrumentation, so Basie approached Neal Hefti and Nat Pierce, who began cranking out arrangements. They both had a light, melody-driven style that was infectious and perfectly suited to the band. By the end of that year, record producer Norman Granz signed Basie to his Clef label. From 1952 to 1954, Basie appeared regularly at Birdland as well as other concert and club venues in New York while recording for Granz. In 1955, as the 10-inch LP was giving way to the 12-inch album, Granz recorded Basie’s first successful release in the larger format—April in Paris, with tenor saxophonist Frank Foster writing most of the arrangements, along with guitarist Freddie Green and Ernie Wilkins. From this point forward, Basie's New Testament band would record one hit album after the next that captured the sound of modernity without losing the essence or soul of the Old Testament band. To quote Marc Myers, “In retrospect, Neal Hefti was the band's main designer—the arranger who relaxed the Basie style much the way building architects of the period worked in glass and steel instead of stone. Hefti's first Basie arrangement was Neal's Deal, for Basie's octet in 1950. Hefti's first full-fledged New Testament band arrangement was Little Pony in 1951, a song title that may have been a reference to Basie's love of the racetrack.” [3] From that arrangement on, Hefti, along with Nat Pierce and those who followed, adhered to a simple guiding principle: craft a catchy melody, have the band's sections play with that melody, let Basie be the band's accent rather than its relentless driving engine, use space for suspense, and build toward an intense, brassy climax at the end. Count Basie's New Testament band was a direct reflection of the bandleader's think-big swing concept and wry sense of humor. But its success owes a great deal to a cast of characters not generally celebrated. If it wasn't for Billy Eckstine's needling, Morris Levy's Birdland offer, Charlie Fowlkes's musician choices, Neal Hefti's and Nat Pierce's arrangements, and Norman Granz's record label, Basie may have faded away like so many other band leaders of the Swing era or simply performed in the old style as a nostalgia act. Instead, the Basie band became the envy of foundering bandleaders and ignited a new Big Band concert era in the 1950s and 60s. [1] <www.jazzwax.com> [2] University Press of Mississippi, 2016. ISBN 9781496805713 [3] <http://www.jazzwax.com/2017/11/basies-new-testament-band.html> |

Copyright ©2024 Seacoast Jazz Society, All Rights Reserved